This article is an adaptation of the talk I gave at the EIT Climate KIC Community Summit in Hamburg (July 2019)

Here’s a parable you’ve probably heard:

In the 1890s New York City had a daunting horse manure problem. Transporting people and goods around the city resulted in so much manure that officials worried that the streets would soon be buried deep in it. Apparently in 1898 there was a conference to address the problem in which they essentially gave up.

Of course everyone knows what happened next. Along came the car and the electric tramway, and boom! Problem solved.

This tale was popularized in the climate change section of Levitt and Dubner’s book Superfreakonomics. The authors used this story to illustrate the value of looking at a problem from a different perspective, also known as “thinking outside the box.”

But I don’t think the story really is a good example of approaching a problem in an original way. The people who developed the car and other types of horseless vehicles weren’t specifically trying to solve the problem of urban horse manure. They were developing a technology that’s better in a lot of different ways — and what they came up with was so much better that it essentially wiped out the earlier solution of using horses for ordinary transportation. In modern terms, the new technology “disrupted” the old one.

The fact that it solved the urban horse manure problem was something of an accidental/incidental side-effect of that disruption.

Tech is Magic! image copyright © C.L. Hamer

Tech is Magic! image copyright © C.L. Hamer

The story resonates today because disruption is the story of our modern lives. When my dad went to engineering school, he used a slide rule for his calculations. But when I was growing up, I never saw a slide rule — didn’t even know what one looked like — because by the time I came around it had already been replaced by the calculator.

Similarly, when I was a kid, if I wanted to know a random fact, I’d look it up in the encyclopedia. At the time I had no idea that — of all the random things in my home — the encyclopedia would become obsolete in my lifetime.

My kids have never sat through a re-run just because there’s nothing else on — they’ve never known a world where you can’t just choose your entertainment any time you want it.

It’s easy to see technology as something that constantly makes our lives better and better — not only solving our problems, but solving problems we weren’t even aware of — in completely unexpected ways!

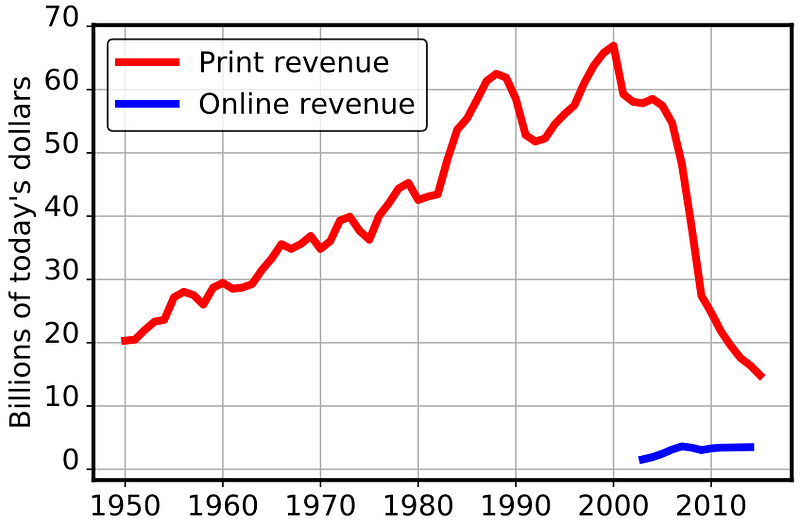

But disruption can be a mixed bag. Consider the case of classified ads:

Classified were small newspaper ads of just a few lines that were classified into categories. They were generally placed by individuals or companies offering a few limited items to a small audience of people interested in the specific thing.

This type of advertising is incredibly inefficient. Depending on the circulation of the paper, a particular ad may be printed thousands of times when only a handful of readers had any interest in the thing being advertised. They’re also limited in space and time. So if I’m offering something very specific, maybe the person who really wants it lives in a different city or only starts looking for it in the newspaper the week after I’ve given up and stopped running my ad — so we’re both out of luck.

The Internet is infinitely more efficient at matching up people who have specific things with the people who want those things. On certain sites your ad may be available to millions of people around the world without an individual slip of paper being printed for each one of them. Searching is nearly instantaneous. And keeping the ad live and available indefinitely costs next to nothing in terms of resources.

This increase in efficiency helps facilitate a circular economy. The Internet makes it so cheap and convenient to lend out random household objects for fun and profit that there’s hardly any reason not to sell, rent, or give away items that you’re not using — which means that more people have access to these items while fewer need to be produced.

So, “yay!” right?

Well, yes and no. The problem is that newspapers depended on those ad revenues. They were their bread and butter. Newspapers’ profits took a terrifying nosedive around 2010 — wiping out huge segments of independent and local journalism and accelerating the consolidation of what remains. This is deadly dangerous for democracy. If most City Halls don’t have a reporter covering them anymore, then there’s nobody to shine a light on what they’re doing. The Washington Post’s new motto is right: “Democracy dies in darkness.”

So, in this case, a disruptive technology wiped out an existing system — and it solved a bunch of problems that we didn’t know we had — in an amazing and unexpected way! It simultaneously created a new and horrible problem that nobody predicted and that we have no idea how to solve.

When you look at your smartphone, and you think about all of the amazing things it can do and the amazing ways it has changed your life, it’s hard to avoid the impression that technology can do anything. Indeed, I first heard the opening parable about horse manure from a friend who was arguing against the need for regulations to protect the environment. He basically seemed to think it was absurd to worry about muggle problems like horse manure or greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere when we have the magic of technology.

Yeah, maybe some amazing new technology will arise that by luck happens to fix our climate catastrophe. That would be great. But I wouldn’t bet my life on it. I wouldn’t bet all of our lives on that happening.

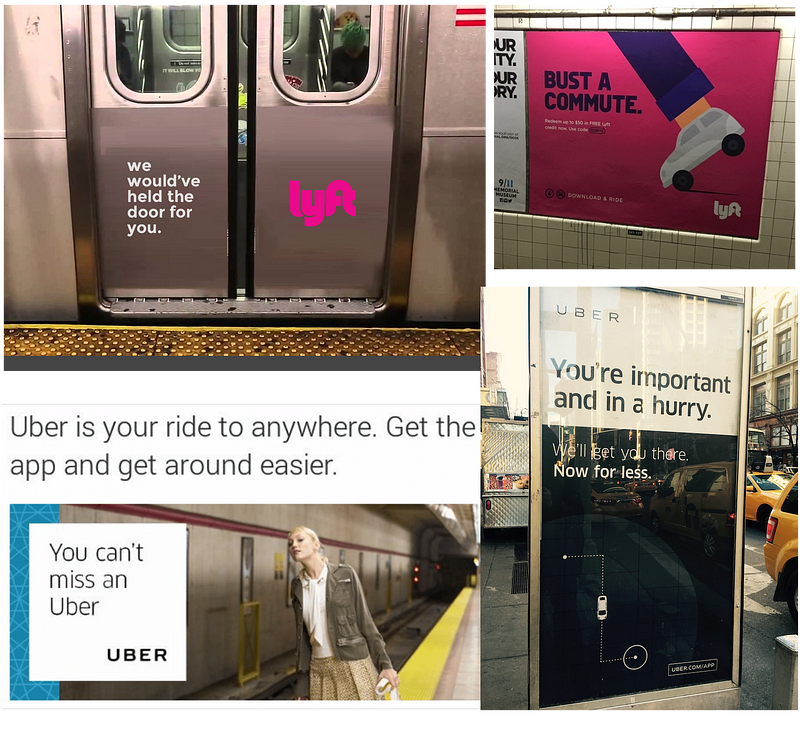

In some ways the “disruption” narrative has become the new “box” that it’s hard to think outside of — and expecting that new innovations will wipe out earlier systems can itself be counter-productive. One example of that is rideshare apps and urban transit.

I’m willing to believe that the technology behind Uber and Lyft is better than ordinary taxi-dispatching software. But is it an order of magnitude better? Is it really like the difference between a car and a horse or classified ads and the Internet? Yet the disruption narrative allows tech companies to keep reinventing the bus and the subway — and to successfully convince people that they’ve come up with something really new.

The expectation that new technologies should disrupt and replace existing technologies justifies rideshare app companies failing to cooperate with municipalities and even actively competing with more efficient solutions like public transportation — since the sexy new technology is supposed to just wipe out the old, unsexy solutions.

Even though ridesharing in cars is increases the number of vehicles on the road and is generally less efficient than public transportation in urban areas, the disruption narrative gives this techy new solution a leg up to compete. After all, if the cars in your fleet aren’t “taxis” and their drivers aren’t “employees” then there are no laws governing the totally new thing you’ve just invented. Disruptive technologies get to live in a sort of virtual international waters where annoying rules about exacerbating rush-hour congestion or paying your workers minimum wage don’t exist.

Unfortunately, in my years in tech startups, I’ve found that entrepreneurs and tech people and a lot of the general public often have a strong faith in the ability of technology alone to solve our problems — a faith that is as unjustified as it is unhelpful.

Consider the case of renewable energy. From a tech alone perspective, it’s already cheaper than burning fossil fuels — and has the added advantages of never running out and not rendering our one-and-only atmosphere unfit for human habitation.

So where’s the disruption? Why are we still burning fossil fuels? Why hasn’t the sexy new technology swept the old one away?

Those are the questions we need to answer. We can’t expect a new technology to automatically disrupt the old industry just because it’s more efficient and better in pretty much every way — sometimes we have to analyze a problem deliberately and intentionally in order to solve it.

That’s why I’m thrilled to have had the opportunity to assist with EIT Climate KIC’s “The Journey” program, and I’m especially thrilled that the focus in 2019 has been on driving systemic change.

In the case of fossil fuels, one of the problems is that there are a number of people and organizations that have grown very rich and very powerful by selling them — and they’re not about to give that up just because their industry is poised to kill us all. They are in the process of deploying all of their wealth and power to defang any attempts to make them pay the real costs of burning carbon — and have even managed to get countries to subsidize their dirty and deadly industry to the tune of billions.

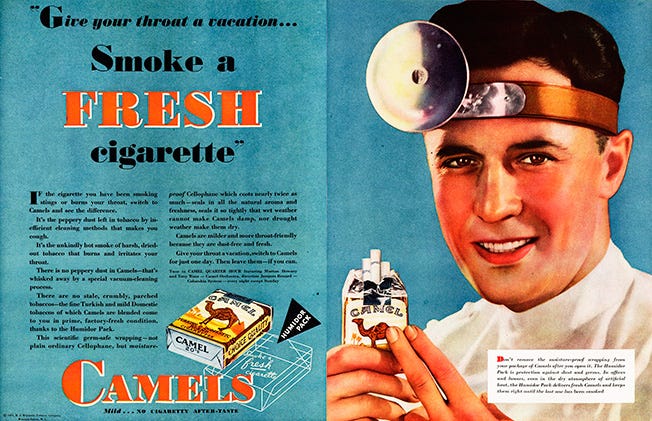

The comparison with tobacco companies should help people today recognize what fossil fuel companies are doing in terms of misrepresentation and misinformation about science:

But it’s not a trivial matter to go from this realization to getting people to take back the power and insist on an immediate end to fossil fuel subsidies and a major shift to renewables now.

That’s just one of the approaches we can take in analyzing and tackling our climate crisis.

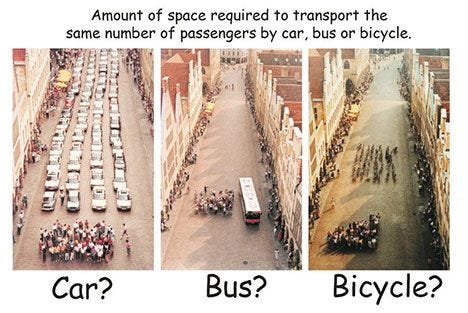

Another approach is to identify inefficiencies in various systems and encourage the use of more efficient alternatives. For example, there are some obvious inefficiencies we can address when it comes to transportation:

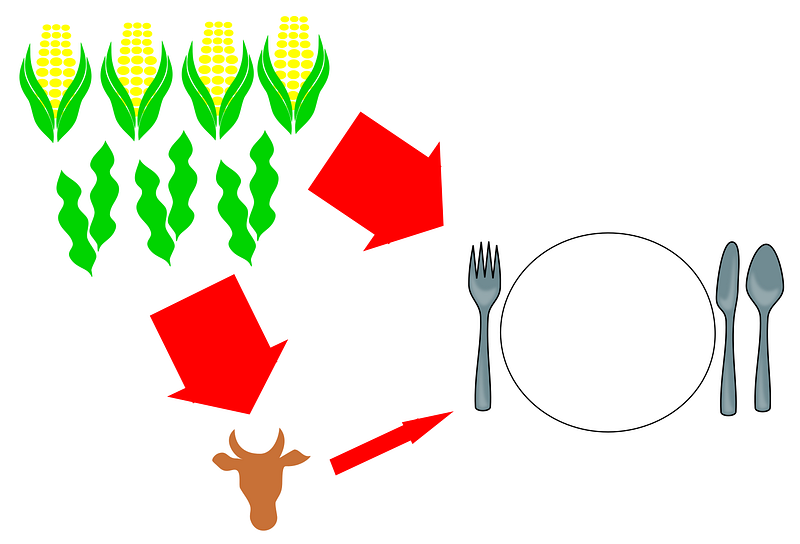

And similar obvious improvements when it comes to food:

At Eaternity, we empower people with detailed information about which meals are more climate-friendly than others. And we’ve done projects with various restaurants in which they’ve reduced their carbon footprint by up to 40% — without any decrease in customer satisfaction.

But the problem is that this improvement required the restaurant managers to be motivated to make an effort to make a change. Yes, it is fantastic when motivated people chose to make changes in their own lives. Of course you kind of have to start with the most motivated people — they represent a critical first step, but they’re not enough. We need a way to spread these sorts of changes across all of society — especially at the highest levels of power — as quickly as possible.

It’s an amazing tragedy about our species that we’re smart enough to be able to destroy the environment that sustains us, but are we smart enough not to?

That’s the question — that’s the challenge — that we have to face head-on. And I wish us all the best of luck.